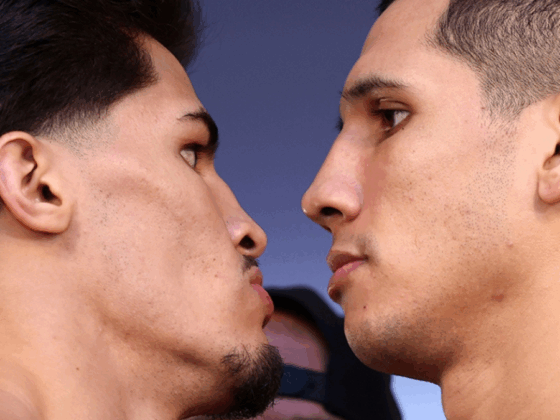

The little hand and the big hand of the clock were inching toward the five as a smattering of city buses, Ubers, and family cars played a monotonous game of “Red Light, Green Light” along Georgia Avenue. The sky is gray, the occasional gust of wind is unforgiving, and the temperature sits somewhere between the manageable winter day Al Roker forecasted and being able to see the breath of the person standing at the bus stop. Steps away from early rush hour traffic and the hustle and bustle of northwest Washington, D.C., a few hundred fans of the sweet science pilec into Howard University’s Burr Gymnasium, staring at the platform positioned at the center of the hardwood.

“Welcome to Howard University,” Howard University Athletic Director Kery Davis said as he stood at the podium.

Gatherings of this size at this location typically don’t happen for much other than homecoming, graduation, a basketball game, or a concert. While the university’s annual fashion show and other festivities are two months in the rearview mirror, it was a homecoming of sorts at The Mecca. Two of the region’s most prolific pugilistic practitioners, Baltimore’s Gervonta “Tank” Davis and Washington, D.C.’s Lamont Roach Jr, gathered the area’s boxing community for a press conference promoting their March 1st fight at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn.

“For 17 years, I worked at HBO, and for 14 of those years, I was [the] head of HBO Boxing,” Kery Davis continued. “That was one of the highlights of my life. I have to tell you that I often get asked, ‘Do you miss it?’ The answer is [that] sometimes, I really do. [Many of] the [boxers] that I often came across when I was at HBO were the most conscientious, disciplined, and courageous athletes that you will ever meet. And a big boxing event, there is nothing like that energy. There is nothing like that environment. That’s why we’re proud to be a small part of what will be a huge boxing event at [the] Barclays [Center].”

Significant boxing events in the District of Columbia have become scarce in recent years, with only one pay-per-view event on a major broadcast station within city limits in the last ten years. However, the energy Davis referred to isn’t all that unfamiliar to the university. Dating back to the 1930s, more than a dozen historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Howard University, Hampton, and Morgan State, among others, fielded boxing teams. By 1936, HBCU boxing and wrestling clubs competed in tandem at the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) tournaments in the spring. From Freager Sanders Jr. at Winston-Salem State University (WSSU) to North Carolina A&T University’s Roland Walton, the CIAA and the broader HBCU boxing community produced fighters that would routinely compete in national tournaments. However, the momentum boxing gained at HBCUs slowly dissipated in the early 1960s when the NCAA stepped back from sanctioning the sport. By the late 1970s, the National Collegiate Boxing Association had taken over as the leading sanctioning body, but many HBCUs were unable to field teams as funding became increasingly scarce and concerns about health and safety grew. Since then, basketball and football have firmly cemented their place as the two most popular sports at most HBCUs and PWIs, but boxing may be on its way back to the forefront.

In 2020, the spread of COVID-19 forced friends and family to distance themselves in precaution, but the sport of boxing brought students together in a time of separation. Jacobey Bell, a student at Morehouse College, moved to Atlanta, Georgia, in 2020 as he started his college career. Three hours away from his siblings, Bell found comfort away from home in the sport of boxing and it blossomed into something bigger.

“When I came to Morehouse my freshman year, my entire family moved to Savannah, Georgia, three hours away. I have three siblings who have been my best friends my whole life, so being without them was tough. I had to find a new family. That’s how the boxing club started,” Bell said. “I sent a message in the class of 2024-2025 group chat saying, ‘Hey, I’ll be downstairs boxing at the dorms today if anyone wants to join.’ Each day, more people showed up. One day, we had about 200 people watching us spar. We got in trouble because it was during COVID, but the school saw the potential.”

Bell’s text and the subsequent training sessions have transformed into the Morehouse Boxing Club, a fully functional student-run organization in the Atlanta University Center (AUC), providing members an opportunity to train and build a community that expands beyond the ring. In the words of Moni G.G., a student at nearby Clark Atlanta University, the Morehouse Boxing Club “is like a family.”

“We help each other beyond boxing. We study together, watch fights, and train at other gyms on Saturdays. The school doesn’t cover those extra training sessions, but we’re so passionate that we make it happen. The club has given me a safe, productive space in college where I feel truly supported,” Moni explained. “It’s about more than boxing—it’s about family.”

Much like Jacobey, Moni was miles away from where she grew up in Samoa and quickly found a family-like atmosphere in the Morehouse Boxing Club. As she became comfortable around the young men she now describes as “brothers,” her confidence in the ring also strengthened. With Jacobey and the club’s leadership organizing tournaments with nearby schools like Georgia State and Kennesaw State, she stepped up to the plate and began competing.

“I remember the exact moment. Kaleb, my coach, and I train together almost every day. One day, I was frustrated because I wasn’t pushing myself hard enough. I was too hesitant, too nice. Kaleb pulled me aside after practice and told me, ‘Boxing is unforgiving. You can’t take it lightly or always put others ahead of yourself. In this sport, people who don’t fight for themselves—don’t win. And I know you want to win,'” Moni recalled. “That was a wake-up call. I realized I had to take myself seriously, and once I did, my confidence grew. The people in this club believe in me more than I believed in myself, and that has been life-changing.”

Moni became even more confident in the ring as time passed, and she had the opportunity to learn from other fighters, including three-division undisputed champion Claressa Shields. Before dethroning Danielle Perkins in Detroit on Sunday, February 3, the Flint, Michigan native traveled to Atlanta, Georgia, and held an open workout with members of the Morehouse Boxing Club, an experience Moni will never forget.

“That was an unbelievable experience. I haven’t even had my first fight yet, and I got to meet the greatest female boxer of all time. That’s crazy,” Moni said. “Initially, I thought I was just there to take pictures since I help with the club’s [social] media [channels/accounts]. But then Jacobey called me and said, ‘Do you have workout clothes?’ Luckily, I was wearing them under my dress. He told me I’d be getting in the ring with Claressa for shadowboxing. That was surreal.”

Shields is not the only world champion pouring her time and experience back into the HBCU community. As Jacobey, Moni, and their AUC classmates trained, sparred, and organized tournaments with nearby colleges, International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee James Toney and double HBCU graduate Matthew Prince King were helping co-found the HBCU Boxing League.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, King, like millions of others, tuned in to watch Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr. compete in an eight-round boxing exhibition. While Tyson nor Jones Jr. endured noticeable injuries, King, like many others, was concerned about the health of two former champions stepping into the ring at their age. Instead of seeing legendary boxers step into the ring in their 50s and 60s, King imagined a scenario where former champions could transition into coaching like Deion Sanders in football and Tyronn Lue in basketball.

“Once I, [a member of Toney’s management team] started traveling for these [boxing] events, I found myself surrounded by boxing legends—Chris Byrd, Ray Mercer, James, Lamon Brewster, Evander Holyfield—just to name a few. While talking with them, I pitched the idea: ‘Why don’t we start a boxing league that gives you all a Deion Sanders moment?’ Just like Deion brought attention to HBCU football, we could do the same for boxing,” King explained. “The students would gain structured programs, and the legends would have a new purpose as mentors and coaches.”

King, Toney, and the league’s leadership have spent the better part of the last three years building relationships with boxing gyms near HBCUs, recruiting boxers, and identifying potential coaches. This summer, King says the HBCU Boxing League will take the next step by setting up clubs at all participating HBCUs. However, a major hurdle still exists — financial backing and infrastructure.

College athletics is becoming increasingly expensive for many institutions, especially HBCUs. In 2023, Division I institutions reportedly spent over $19 billion on athletics, a 12% increase from the previous year. However, the difference in median net operating results (or deficit) between the FBS autonomy and nonautonomy schools were over $17 million. Division I and lower-level HBCUs are not exempt from these financial troubles. Talladega College in Florida recently was forced to cut six sports due to financial constraints. Tennessee State was forced to withdraw from the Heritage Classic due to “financial issues.” Prince and the HBCU Boxing League have attempted to combat the anticipated financial limitations participating schools may have by partnering with VYRE Network, a leading free global streaming platform, Triad Entertainment, to stream the HBCU Boxing League’s initial season. Moving forward, the league aims to connect with influential celebrities in the boxing community and various streaming platforms to amplify its coaches and student-athletes.

“These moves are critical because we’re positioning this league as a viable alternative, especially with the current instability in Olympic boxing. College athletics is changing—athletes can now get paid, sports betting is legal, and NIL deals are in play. It’s the perfect time to introduce this concept,” Prince expressed. “The goal is to create marketable fighters. Right now, many fans don’t know top boxers until they’re 30+ years old. That’s not sustainable. College sports create stars early—by the time an NBA or NFL player gets drafted, they already have millions in endorsements. We want to replicate that model in boxing by giving athletes exposure from the start.”

Building boxing clubs at HBCUs, bringing in former champions to coach student-athletes, and establishing partnerships with brands and public figures are all steps the HBCU Boxing Lague is taking to achieve its ultimate goal — restoring the legacy of HBCU boxing. With the work that Jacobey, Moni, and students at HBCUs are doing, significant progress has been made, but King is hopeful that things can go even further.

“We want to be on par with college basketball and football, with HBCUs becoming the powerhouses of college boxing. The goal is for future top fighters to look at Howard, Texas Southern, or Jackson State first, knowing that these schools offer the best opportunities. A college boxer should be able to make more money in school than in their first four years as a pro. They should be able to build a fan base, train under legendary champions, and develop their careers the right way,” King said. “As for support, PR is key. We need visibility—media coverage, brand partnerships, and community engagement. If people help spread the word, we can turn this into something massive.”