Right now, Stephen Curry is the biggest star in the NBA and he might quite possibly be the first unanimous MVP award winner in NBA history. Curry’s stardom came to light slowly but surely and at first, not everyone saw it coming. With solidified stars in LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Carmelo Anthony, Dwyane Wade and Chris Paul, dominating a majority of the past decade, there appeared to be no room for more guys at the top. That is until Stephen Curry broke through the door.

Curry’s explosion to the top might not have been expected by many experts, fans or even sneaker executives. Those execs at the top company, Nike, possibly didn’t seriously consider that Curry was going to be the next big thing and that might now be bad for their brand. A $14 billion dollar blunder which now works out for Under Armour.

Ethan Sherwood Strauss of ESPN paints the picture of how the sneaker giant royally screwed up Stephen Curry’s presentation back in 2013.

IN THE 2013 offseason — coming off a year in which Curry had started 78 games and the Warriors had made the Western Conference semis — Nike owned the first opportunity to keep Curry. It was its privilege as the incumbent with an advantage that extended beyond vast resources. “I was with them for years,” Curry says. “It’s kind of a weird process being pitched by the company you’re already with. There was some familiar faces in there.”

Curry was a Nike athlete long before 2013, though. His godfather, Greg Brink, works for Nike. He wore the shoes growing up, sported the swoosh at Davidson. In his breakout 54-point game at Madison Square Garden on Feb. 28, 2013, he was wearing Nike Zoom Hyperfuse, a pair of sneakers he still owns, tucked away in his East Bay Area home, shielded from the light of day. “They’re not up front and center,” Curry says of the pair. “I definitely kept all my favorite [shoes] just as a memory of where my career has gone.”

Nike had every advantage when it came to keeping Curry. Incumbency is a massive recruiting edge for a shoe company, as players often express a loyalty to these brands their NBA franchises might envy. And Nike wasn’t just any shoe company. It’s the shoe company that claims cultural and monetary dominance over the sneaker market. According to Nick DePaula of The Vertical, Nike has signed 68 percent of NBA players, more than 74 percent if you include Nike’s Jordan Brand subsidiary. In the 2012 Olympics, Mike Krzyzewski, a Nike endorser, coached an entire roster of 11 Nike-signed athletes and Kevin Love, who merely wore the shoes.

Its hold on consumers is even tighter. According to Forbes, Nike accounted for 95.5 percent of the basketball sneaker market in 2014. In short, its grip on the NBA universe is reflective of a corporation claiming Michael Jordan heritage and a $100 billion market cap — all advantages that might explain why Nike’s pitch to Curry evoked something hastily thrown together by a hungover college student.

The August meeting took place on the second floor of the Oakland Marriott, three levels below Golden State’s practice facility. Famed Nike power broker and LeBron James adviser Lynn Merritt was not present, a possible indication of the priority — or lack thereof — that Nike was placing on the meeting. Instead, Nico Harrison, a sports marketing director at the time, ran the meeting (Harrison, who has since been named Nike’s vice president of North America basketball operations, did not respond to multiple interview requests).

In truth, there had been other indications that Nike lacked interest before this meeting. There was the matter of whether Curry would get to lead a Nike-sponsored camp for up-and-coming players. These camps aren’t high on the list of fan concerns, but they matter deeply to the game’s elite. They’re a chance to teach a younger generation, to have interactions more meaningful than strangers clamoring for autographs on the street.

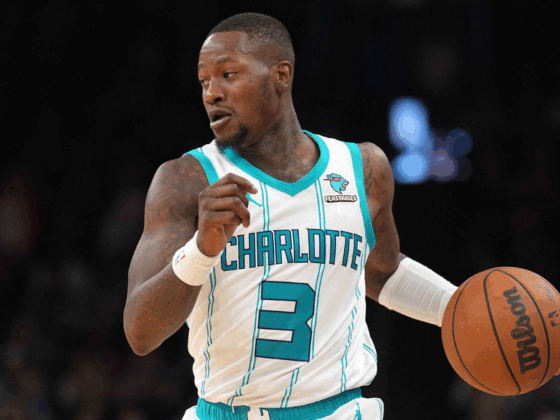

Getting to run such a camp meant something to Curry, in part because participating in one meant something to him. When he was younger, Curry had gone to Chris Paul’s camp and the experience made a lasting impression. Says Curry’s friend and former roommate Chris Strachan, “He was always at Chris Paul’s camps as a young guy, and he always looked up to Chris Paul. He took a lot of the stuff that CP does with film sessions and he implemented it.”

Strachan recalls of 2013, “That summer, when it was really decision time, [Nike] were looking at Kyrie Irving and Anthony Davis coming up. They gave Kyrie a camp and they gave Anthony Davis a camp. They didn’t give Steph a camp.”

The pitch meeting, according to Steph’s father Dell, who was present, kicked off with one Nike official accidentally addressing Stephen as “Steph-on,” the moniker, of course, of Steve Urkel’s alter ego in Family Matters. “I heard some people pronounce his name wrong before,” says Dell Curry. “I wasn’t surprised. I was surprised that I didn’t get a correction.”

It got worse from there. A PowerPoint slide featured Kevin Durant’s name, presumably left on by accident, presumably residue from repurposed materials. “I stopped paying attention after that,” Dell says. Though Dell resolved to “keep a poker face,” throughout the entirety of the pitch, the decision to leave Nike was in the works.

In the meeting, according to Dell, there was never a strong indication that Steph would become a signature athlete with Nike. “They have certain tiers of athletes,” Dell says. “They have Kobe, LeBron and Durant, who were their three main guys. If he signed back with them, we’re on that second tier.”

Dell makes an analogy back to the past, when Dell’s alma mater, Virginia Tech, offered his son the mere opportunity try out as a walk-on. This was familiar territory for a player who’d long prevailed over projections. “Wasn’t highly recruited, wasn’t highly respected, wasn’t highly thought of,” Dell says. “It was kind of like that, you know?”

Dell’s message for his son was succinct: “Don’t be afraid to try something new.” Steph Curry had thrived on proving people wrong for the entirety of his career. He had delighted in it, even. And Nike was giving him fuel.