There’s something disheartening and frightening about watching a young adult step into the house of their dreams, only to learn that it is haunted. Justin Tipping’s HIM understands this in a disturbingly evocative way, explores it, and ultimately comes to a bloody, messy conclusion.

Only looking at the cover, the Jordan Peele-produced feature is a horror-thriller about football, but a deeper dive into the playbook reveals it’s a bold statement about our society’s relationship with football, celebrity, power, and work-life balance.

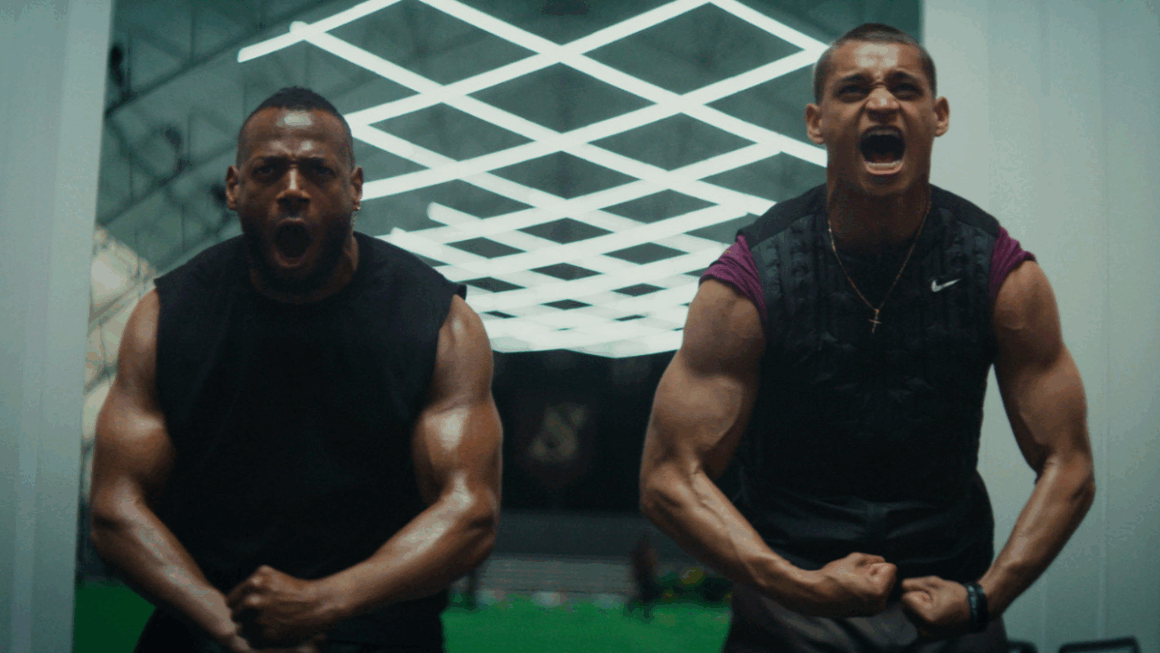

Tipping and Peele entrust the tried and true talent of Marlon Wayans and the promise and ambition of Tyriq Withers to deliver their message. Withers bursts out of the huddle and onto the big screen for his breakout role as Cameron Cade, a surefire gunslinger who has dedicated his life to football and is now expected to be selected first overall in the NFL Draft. However, his dreams of NFL glory are put into jeopardy when he ominously suffers a head injury that could derail his goals in the short term and potentially end his career in the long run. Just when things seem to be slipping through his fingers, he’s offered the opportunity to spend a week training with Isaiah “Zay” White, a star quarterback who bounced back from a leg injury reminiscent of Louisville’s Kevin Ware to become an eight-time champion and the type of man Cade’s late father would like him to model himself after. If he impresses White, he could still get drafted and live out his dreams. Unfortunate for Cade, he quickly discovers that something sinister exists deep within the fabric of America’s pastime, giving new meaning to the phrase — “God. Family. Football.” Through bloody tough practices, insane encounters with…insane fans, and bonding time with his idol that gives new meaning to the term “Target Practice,” Withers’ Cade is left asking himself, “Is it worth it? What (or who) am I willing to sacrifice to achieve success?”

HIM isn’t solely about football, but rather, the nation’s relationship with the game and the people who play it sits at the heart of the film. Football, for so many of us, has always been a gateway—a way out of the block, a way into the world. But it’s also a machine. And what HIM renders with chilling clarity is how that machine runs on the bodies, and sometimes the souls, of young men too hungry or broken to walk away. Those who stay on the field leave pieces of themselves that are buried beneath the turf, never to be found again. Those who walk away are ridiculed into an obscured existence riddled with ostracism and attacks on their manhood.

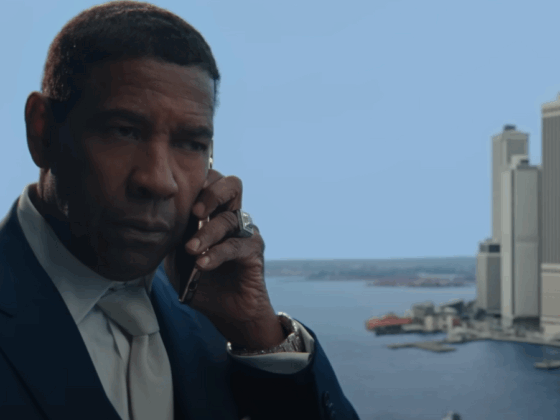

Wayans’ White is the former, not the latter. His trophy case is full and his days are full of extreme rehab, brutal training, and a twisted chase toward what he perceives as greatness. In the shoes of this fictional quarterback, Wayans, best known for his comedic chops, summons a darkness that he rarely has the opportunity to showcase. His quarterback is less coach than cult leader, promising greatness while bending the boy in his care toward something far more sinister. Yet, he manages to have a keen understanding of his own mortality despite his fame tricking him into believing he is, at times, a deity himself among the American public. His performances amplify the echoes of every sideline sermon we’ve heard—about toughness, about sacrifice, about “paying the price.” Only here, stripped of Sunday spectacle, those sermons look like madness and murder, both metaphorical and literal.

This madness is best not only personified by White and those on the field, but by those around him. Wayans’ doctor, Marco (Jim Jefferies), sees his star client more than he likely sees his own mother in an attempt to remain at White’s side and become known as the best in his profession. Wayans’ biggest fan, Marjorie (Naomi Grossman), spends more time worshipping at the proverbial altar of a pigskin than pursuing her own dreams (if she has any). The public’s obssession with this game, their own personal success in relation to it, and the identity often derived from it are up for an official’s review as much as White and Cade are.

How many of us have become so obsessed with success that it consumed a piece of us? What are we willing to sacrifice to be the one that people are cheering for, applauding or even handing a trophy to? Why have we become so entranced by a children’s game that some of us align our entire personal identity with our favorite teams, athletes, entertainers and public figures? As these questions sit on the screen, it’s hard not to think about how many of us were raised on football as a proving ground. Pop Warner in the park. Friday night lights under aluminum bleachers. Sundays in the barbershop, the TV blaring highlights, the old heads talking about who had heart and who didn’t. HIM takes that mythology and asks—what if our hearts and our humanity were the sacrifice all along?

Tipping and Peele’s feature does not always answer that question directly and clearly. At times, pieces of Withers’ back story feel rushed or underdeveloped in order to move the film along at a faster pace. But its central focus—the way institutions recruit, consume, and discard young men….young BLACK men and how it displays the idea of success to them—is urgent and deeply felt. Tyriq Withers, carries that weight beautifully, shifting between hope and horror with a rawness that makes you remember how fragile true happiness and fulfillment through career ambition is.

HIM doesn’t just scare you with shadows in a mansion. It scares you with something more familiar: the cost of wanting to be great in a country that too often confuses greatness and success with domination, sacrifice, and destruction.