Chris Paul has been the target of jokes among even some of the most ardent NBA fans for a few reasons. His no nonsense attitude has the effect of turning people off of him as does his, shall we say eccentric, drawing of fouls. The most common criticism, of course, has been his inability to lead teams past the second round of the postseason both in New Orleans and in Los Angeles.

But when it comes to individual accomplishments, Paul’s impact on his teams cannot be overstated. For his career, Paul has averaged 18.7 points and 9.9 assists per game, one of only five players in NBA history surpassing 18 and 9 for their entire career. On Sunday, he surpassed 8000 assists for his career, ranking tenth in NBA history.

Nevertheless, the beauty of Chris Paul is not through his individual statistics, no matter how incredible they may be. Paul’s brilliance comes through how he runs an entire offense as the proverbial coach on the floor. His ability to read the defense and always be a step ahead has created numerous opportunities and countless highly-efficient offenses during his illustrious career. Case in point, Paul’s teams (including two sub-par ones to begin his career) have had an average offensive rating of 108.6, a number that would rank as the seventh best offense in the NBA today.

There is no perfect way to encapsulate Paul’s ability but there are numerous measures to put it into context. One way to show the quality of shots that Paul has created for teammates is to look at his teams’ weighted true shooting percentages – that is averaging teammates’ TS% (which weighs three point shots and free throws accordingly) and weighing each player’s percentage through the number of shots he took. There is obvious context missed here: it does not account for shots not created by Paul and it does not adjust for the quality of his teammates.

Nevertheless, with high usage players who create the majority of shots, that could be an interesting tool to see how offenses are run. Looking at Paul’s weighted teammate true shooting percentages shows a fairly common sense fact: his teams have shot the ball well and have been much better with the Clippers where the quality of teammates has been vastly superior.

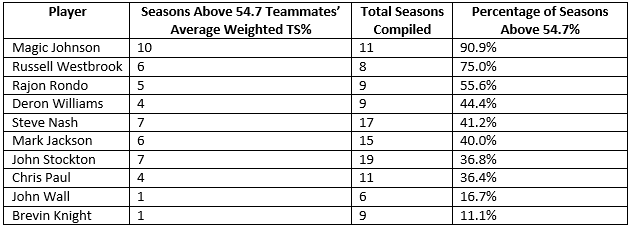

Of course, a series of dots on a plot do not mean anything without context, so I completed the same process for the ten players with the highest career assist percentages in league history, for whom the error of using such a metric is lower (Paul is second on that list at 47.2 percent).

For added context, one can use the 2016-17 season’s numbers as a baseline comparison. This year has featured the best offensive basketball in league history with several historically efficient units. On average, teams have a true shooting percentage of 54.7 percent. Tabulating the number of seasons each of these point guards accumulated with an average teammates’ weighted true shooting percentage above that number provides more added context. (Note that some seasons were not compiled as players missed significant time due to injury or were moved mid-season and therefore affected each teammate’s numbers significantly less).

Obviously, this is not particularly great evidence for the “Chris Paul creates the best shots” club but there is important context missing here. For one, Paul’s career has followed an upward trend in this regard; his four highest ranking seasons have come in the past four years. Conversely, Rajon Rondo and Deron Williams have followed downwards trends and are unlikely to keep adding to their total number of seasons above that mark.

John Wall is following a similar trend to Paul but has not had as dynamic of an improvement. Russell Westbrook should follow the same course for some time, but he will be missing Kevin Durant, the teammate that accentuated his great passing seasons moving forward.

Paul’s ranking near John Stockton is actually a fairly good indicator of the type of point guard he is: a remarkably consistent performer as a passer who has made most of his success playing next to one (or two in CP3’s case) dynamic big. This comes with the caveat that Paul has time to surpass Stockton’s percentage of seasons with the adjusted TS% above this year’s average and almost certainly will do so this season. That would move Chris Paul past not only Stockton but also Mark Jackson and Steve Nash and that’s before more of a drop-off from Rondo and Williams is calculated.

Doing so in a year in which Paul has dealt with injuries to himself and his best teammate would add more to Paul’s already fantastic resume. But that legacy will not be complete if he does not win at the highest level.

So why has Paul struggled to have sustained success in the postseason? Is it as simple as playing in an era in which the Western Conference has repeatedly been a bloodbath of high-level competition? His best teams have had the misfortune of being a top team in a league that will likely see the Warriors and Cavaliers meet in the Finals for the third straight year.

But there may be even more behind what has plagued Chris Paul’s career. The archetype that Paul has played so perfectly in his NBA career is one that we have seen many times before: a ball dominant and high-usage point guard who sets up the bulk of his team’s offense. Throughout NBA history, that archetype has had plenty of regular season success but, much like Paul, other similar players have not been able to translate that into the playoffs.

Taking the 50 individual seasons with the highest win shares in which a guard has had an assist percentage of 40 percent or higher effectively showcases this phenomenon. Those 50 seasons had an average winning percentage of .636 (only two missed the playoffs) which falls flatly to .424 in the postseason.

Of course, diminishing win rates are expected; there is a much higher level of competition in the postseason and wins are not racked up against the bottom feeders of the league. Nevertheless, there is more telling evidence. None of those 50 seasons ended with a championship for the player in question and only four (Stockton in 1997, Jason Kidd in 2003, Rondo in 2010, Tony Parker in 2013) resulted in trips to the Finals. Even the Conference Finals are rarities in this scenario with only 15 seasons ending in a trip to the semifinals, despite all of those teams featuring a really good or star-level player.

To some, 50 seasons may not be a fair sample size and that’s a valid point. There is a lot of missing context evident in this discussion. For example, Kidd managing to get a Nets team to the Finals in 2003 is a sign of his brilliance and the success of an offense predicated around his masterful ability to be a floor general. Of course, there is an argument on the other side that a weak Eastern Conference allowed that to happen in a way that may not have been possible at a different time.

The main caveat in this entire theory is of course LeBron James. James is unlike any superstar we have ever seen before: a 6-8 forward who runs an offense like a point guard. James has a career assist percentage of 34.8 percent. In the previous six seasons, in which he has reached the Finals every time, that number has been even higher at 35.3 percent. So far this season, James is assisting on 41.4 percent of teammates’ field goals when on the floor and he is almost guaranteed another berth in the Finals and perhaps another ring.

But perhaps, LeBron is the exception to what seems to be a rule. Perhaps, his individual brilliance as one of the greatest players of all time regardless of position is what has driven him to success despite being the offensive system for the teams he has had so much success with.

Chris Paul, like most guards before him, has not been able to take his individual success and translate it into a top-four finish in the NBA. Does that say more about Paul, his teammates, or the type of offense he has brilliantly run in his time in the NBA? To an extent, it’s a factor of all three as well as the league environment surrounding him.

Ranking the aforementioned 50 seasons by team offensive rating (a measure of how many points scored per 100 possessions to adjust for pace) places only two Chris Paul seasons (2013-14 and 2014-15) in the top 20. Stockton and Nash, two similarly high usage players who had slightly more postseason success, each have three in the top ten.

Paul did also have the misfortune of playing for Byron Scott for several years on the New Orleans Hornets on teams that had mediocre levels of talent surrounding him. Would a better offensive mind coaching him and his teammates result in more success for a younger Paul? It’s possible but not a given and it would shake up the big-picture view of his career as he now prospers with the Clippers.

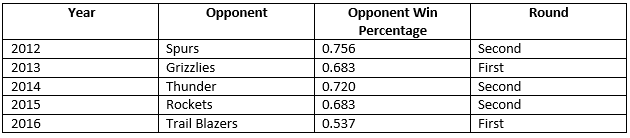

Perhaps the greatest factor in Chris Paul’s lack of success, however, has been the league in which he’s played, particularly in the last few seasons in Los Angeles. Since Paul’s move to LA, the Clippers have lost to the following teams in the postseason:

The only conceivably bad loss in Paul’s postseason career in Los Angeles is against the Trail Blazers but that was in a series in which Chris Paul and Blake Griffin were hurt in game four, paving the way for three straight Portland victories to take the series.

Regardless, the intent here is not to make excuses for Paul and the Clippers. Rather, it’s to question where LAC can go from here. Can they reach the ultimate goal of winning a championship with a core centered on what Chris Paul can do with the ball in his hands?

There is obviously no way of fully predicting that but as history has taught us, it is immensely difficult to win a title or even to get anywhere close to it. So the logical conclusion may be for the Clippers to move away from a Paul-centric offense or at least to temper their reliance on his play.

The Clippers have one huge advantage outside of Chris Paul and that is the playmaking ability of Blake Griffin. At the power forward position, Griffin has the ability to beat nearly any player off the dribble. He can grab rebounds on one end and run the fastbreak. And he has shown a considerable ability to get other players involved when that has been asked of him.

But Griffin’s assist rate has not made considerable strides forward even as his passing has. The reason for that is mainly Chris Paul’s dominance of the ball and an offense that is predicated on simple plays created by its lead guard. The Clippers are right in the middle of the pack in terms of passing this season, ranking 14th in the NBA with 305.2 made per game. There is something to be said about the lack of passing making them a more predictable offense in the postseason, especially when coupled with the fact that nearly everything goes through one player.

The counterpoint to all of this is that any changes may not matter with the Super Warriors looming large in the Western Conference. But the Clippers should be doing everything they can to at least be a consistent WCF team and give themselves a chance should the Warriors face an untimely injury or cold streak.

So what does this mean about Chris Paul’s current season and moving forward? When healthy, Paul has produced at roughly the same level he has since arriving in Los Angeles. The Clippers have been in a free fall to the fourth seed (cratering all the way to seventh in the conference at one point) due to injuries but are clearly a dangerous team and one could argue the biggest threat to Golden State in the Western Conference.

Nevertheless, Paul’s MVP case gets weaker every day the Clippers struggle to keep pace with the Western Conference elite. Barring a huge stretch in the second half of the season when Blake Griffin returns, it seems improbable that the point guard will beat out the likes of Harden and Westbrook for the award.

As far as team success goes, as the years go on and Chris Paul becomes older, it seems more and more evident that winning a long-awaited title would be an upset for the point guard at this point. That shouldn’t mean that Paul’s career is deemed a failure. He is one of the greatest players ever at his position and his individual accomplishments on both ends of the court place among the elites of his generation.

There is still time, of course, as Paul does not appear to be close to slowing down just yet. But if he is to win a ring before he retires in order to cement his legacy among the greats, he may have to change the entire style of play that has been the foundation of his success.

As it becomes more and more unlikely that Chris Paul ever wins a championship as the main cog in a title-team machine, it’s important to realize his greatness in the absence of team success. Paul has managed some of the most efficient and dominant offensive teams in recent memory while doubling as arguably the best defender at his position in this generation. Paul’s legacy has already been cemented as one of the greatest point guards of all time and arguably the greatest player ever to not win an MVP. A ring would remove the final blemish on his resume but even without it, Chris Paul’s legacy is clear.