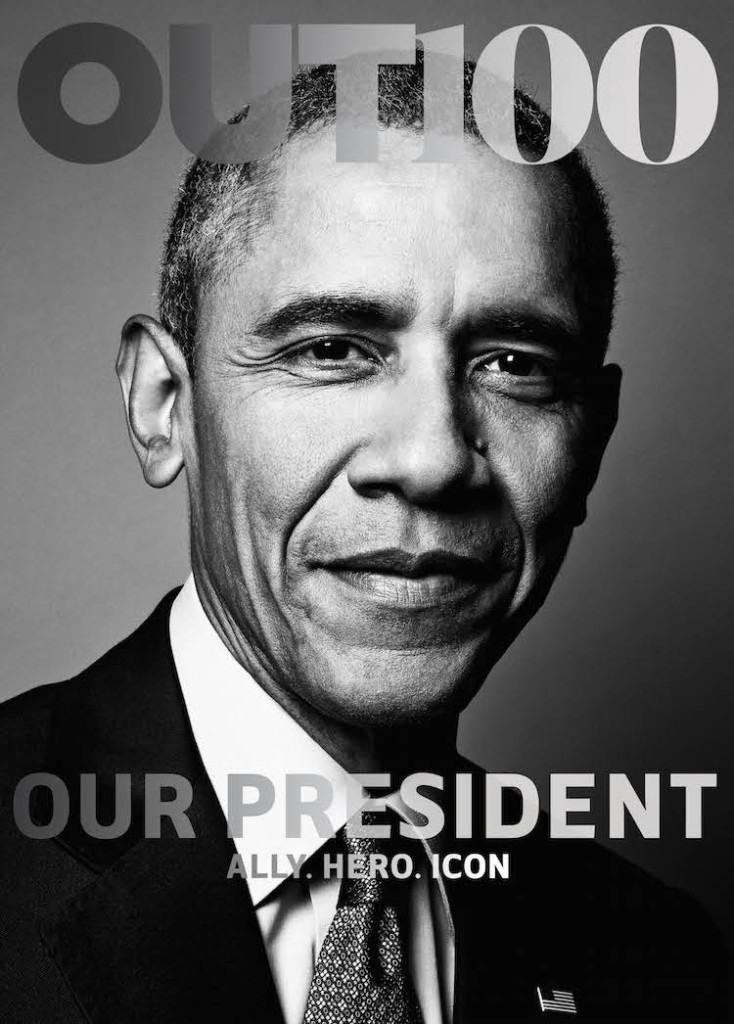

In an unprecedented move, Barack Obama becomes the first sitting commander-in-chief to cover an LGBT magazine. Named Ally of the Year, Out Magazine extolled the 44th President’s stance on marriage equality, the advancement to repel “don’t ask, don’t tell,” and other historical initiative. During the interview, Obama is asked about the first person he knew was gay; when he realized the movement of the LGBT would be a focal point during his administration; Sasha and Malia growing up and possible attitudes toward homosexuality; the Kim Davis situation; and more.

Check out some excerpts below.

Aaron Hicklin: Mr. President, who was the first person you met who you knew was gay?

President Barack Obama: I’m not sure who the first openly gay person I met was, but Dr. Lawrence Goldyn, one of my college professors, is a man who stands out to me. I took his class freshman year at Occidental. I was probably 18 years old — Lawrence was one of the younger professors — and we became good friends. He went out of his way to advise lesbian, gay, and transgender students at Occidental, and keep in mind, this was 1978. That took a lot of courage, a lot of confidence in who you are and what you stand for. I got to recognize Lawrence last year at our Pride Month reception at the White House, and thank him for influencing the way I think about so many of these issues.

When was the moment that you realized that LGBT equality would be a key focus for your administration?

This really goes back to when I was a kid, because my mom instilled in me the strong belief that every person is of equal worth. At the same time, growing up as a black guy with a funny name, I was often reminded of exactly what it felt like to be on the outside. One of the reasons I got involved in politics was to help deliver on our promise that we’re all created equal, and that no one should be excluded from the American dream just because of who they are. That’s why, in the Senate, I supported repealing DOMA [the Defense of Marriage Act]. It’s why, when I ran for president the first time, I publicly asked for the support of the LGBT community, and promised that we could bring about real change for LGBT Americans.

Watching Sasha and Malia grow up, are you conscious of a generational difference in their attitudes to homosexuality versus the generation(s) before them?

Absolutely. To Malia and Sasha and their friends, discrimination in any form against anyone doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t dawn on them that friends who are gay or friends’ parents who are same-sex couples should be treated differently than anyone else. That’s powerful. My sense is that a lot of parents across the country aren’t going to want to sit around the dinner table and try to justify to their kids why a gay teacher or a transgender best friend isn’t quite as equal as someone else. That’s also why it’s so important to end harmful practices like conversion therapy for young people and allow them to be who they are. The next generation is spurring change not just for future generations, but for my generation, too. As president, and as a dad, that makes me proud. It makes me hopeful.

When you were a community organizer in the South Side of Chicago in the 1980s, one of the principal issues was housing. Was the impact of AIDS and HIV a part of that?

In Chicago in the 1980s, as was the case across the country, Americans living with HIV/AIDS were unfairly evicted from their homes, fired from their jobs, and forced to face social, economic, and personal atrocities — which is to say nothing of the health problems they were dealing with. That’s one of the reasons that my administration developed the first-ever comprehensive National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. People living with HIV are benefiting from more effective collaboration across the federal government. By the way, they’re also benefiting from the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which allows for funding increases and groundbreaking new work towards an AIDS-free generation.

In your 2013 inauguration speech you delighted the LGBT community by including Stonewall alongside Seneca Falls and Selma as a touchstone of America’s progressive history. Tell me about the decision to mention Stonewall in the speech.

Part of being American is having a responsibility to stand up for freedom — not just our own freedom, but for everybody’s freedom. Our individual stories come together to make one large American story. Just like Seneca Falls is part of the American story, and Selma is part of the American story, Stonewall is part of the American story, and I thought it was important to say so.

Read the whole interview here.